Coming Full Circle

The Life and Legacy of the Just Family

“To be able to say I am doing a project in this community is humbling; coming full circle, I am doing a restoration project as an African American marine biologist in the birthplace of Ernest Everett Just,” Al George, director of conservation at the Aquarium, expresses to us over Zoom.

The birthplace to which Al is referring to is the former Township of Maryville, today recognized as the Ashleyville-Maryville neighborhoods of Charleston. The significance of Maryville was a consideration in Al’s decision to become the director of conservation five years ago, the first person to ever hold this role. During his tenure, Al’s expertise has challenged us to widen our lens to comprehend, strategize and advocate for change in areas of environmental justice, resilience planning, plastic mitigation and more. Perhaps the most poignant part of his current role is the work he does in the above-mentioned area, the hometown of renowned Black marine biologist, Ernest Everett (E.E.) Just. But who was E.E. Just, and why specifically is he held in such high regard?

A Legacy Begins

E.E. Just’s story cannot be told without first introducing you to his mother, Mary Matthews Just. After all, they shared more than just genetics. Both were pioneers of their time, forging ahead on paths few others had taken before them, motivated by the possibilities of what could be, determined to evoke change. For Mary, that involved independence and a sense of community. For Just, it was scientific discovery.

Back in the 1880s, Mary was a single mother working two jobs. She taught in a local Charleston school and spent her summers working in the phosphate mines on James Island. Having recently lost her husband, a dock builder, Mary set forth to provide for and raise Just and his two younger siblings alone.

Mary had heard of land nearby, a plantation originally owned by the Lords Proprietors in the late 1600s, that now stood vacant. She began to fill the void with her dreams of a self-sustaining Black community, a central hub that could celebrate, embody and preserve the local history and culture. She envisioned residents farming and tending to the land, sowing a sense of place and belonging. Mary swiftly shared these dreams with others in the hopes it could become reality.

Not long after, those dreams took root as the land was divided up into lots and sold off to local Black families. From there, the Maryville township was formed, with Mary herself serving as its namesake. Mary would go on to found a school within the township, continually striving to create a better, brighter future for the next generation.

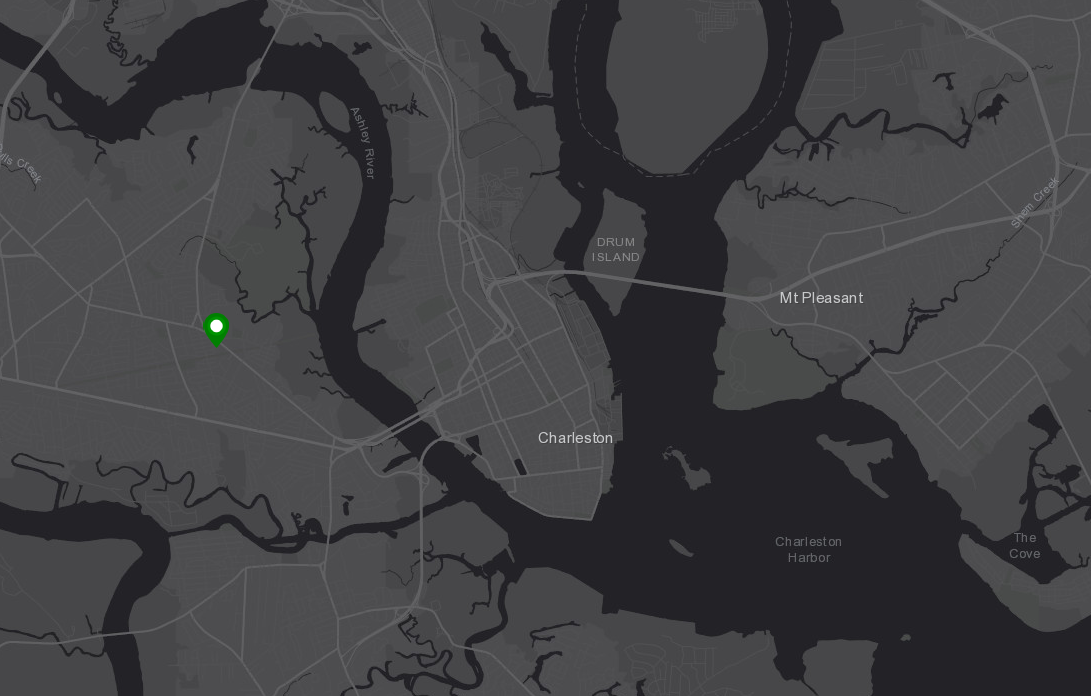

Location of the historic Maryville township

Location of the historic Maryville townshipMaryville shaped the early upbringing of Mary’s eldest son, E.E. Just. It was here we saw a glimpse of the tenacity that would carry on throughout his life. After contracting typhoid fever, Just suffered memory loss severe enough that he had to relearn how to read and write, a feat even Mary questioned if he could achieve.

Realizing her son could have a strong future in academia, Mary sent Just to finish his schooling up north, hoping he’d face less racial bias and receive a better education. Just finished high school a year early with the highest grades in his class and subsequently enrolled at Dartmouth College. After the death of his mother during his high school years, Just never returned to Charleston.

At Dartmouth, Just’s accolades in academia grew. But as graduation approached, discrimination against him did as well. Despite being the only magna cum laude recipient of his class (with honors in zoology, botany, history and sociology), he was denied the opportunity to give the commencement speech, a move allegedly made to diminish attention around his successes.

Ernest Everett Just (Credit: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution)

Ernest Everett Just (Credit: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution)While on the job hunt, Just was once again met with resistance and racial bias. Few colleges welcomed people of color into positions of leadership, regardless of their education or expertise. Just finally landed a job as an English professor at Howard University in Washington, D.C., an historically black college. He went on to become head of the biology and zoology departments. After meeting a colleague from another university, Just was invited to participate in research at the Marine Biological Lab (MBL) in Woods Hole, Mass.

Woods Hole MBL became somewhat of a home base for Just. He spent nearly every summer there, planning and participating in ongoing research primarily in the fields of cytology (cell biology) and embryology (fertilization and development). He was a strong proponent of studying cells in their whole form, rather than a piecemeal approach.

For his job hunt in the States, it didn’t matter how many advances to science Just had on his resume, how many scientific papers he authored or how many awards he received. He was consistently turned down by the larger, predominantly white colleges and universities, his brilliance overshadowed by their biases. Knowing that his career aspirations would be stifled in the States, Just turned to Europe for a better future in hopes that racism wouldn’t follow.

Though Just spent the majority of his career thereafter overseas, his contributions made their way back home to serve future scientists, biologists and students on their own scientific journeys. He is revered and celebrated for his discovery of the importance of a cell’s surface for development. Equally as important is his contribution to the ongoing legacy of the Just family. Just two generations before him, his grandfather was a member of the Free Black Community of Charleston. And one generation after him, his daughter served as a civil rights activist.

Inspiring Future Generations

Just was a driving force behind Al’s own personal career trajectory. He shared these sentiments with one of his professors, Dr. Matt Gilligan (Dr. G) and a fellow classmate at the time, Dr. Dionne Hoskins-Brown (who currently serves as director of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration programs at Savannah State University), among others. It was she who first introduced Dr. G to the life and legacy of Just. “Just has had a profound influence on me, personally, and on my teaching and mentoring career,” Dr. G tells us. “So many of the things that he experienced, the obstacles that he overcame, the circumstances that were insurmountable and his immense contribution to science tell an epic American story of triumph and tragedy.”

From that point on, Dr. G vowed to use his classroom to help reduce racial disparities in the sciences. “For decades, I reserved a lecture in my marine biology course to tell the stories of black and indigenous explorers, scientists and mentors. I hoped that it would inspire all students, not just Black, indigenous and people of color (BIPOC). I believe that it did because some of them were bold enough to offer observations about E.E. Just like, ‘If he could do that then, I can do this now’.”

Al and Dr. G visiting the historic township of Maryville

Al and Dr. G visiting the historic township of MaryvilleThe Just family tree sprouted a forest of fellow scholars who shared a similar work ethic as Just. When Al told Dr. G he had taken the Aquarium role and would be working near the birthplace of Just, he asked to visit and see the community firsthand.

Planting saltmarsh with SCDNR

Planting saltmarsh with SCDNR The present-day location of the historic Maryville township is facing significant environmental stressors from climate change. There’s no longer an abundance of saltmarsh serving as a natural barrier against the changing tides and rising seas, leaving the community exposed. For Al, aiding in the restoration of this community landscape is a personal and professional goal. Last year, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, he began work on a three-year project with the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources to plant ½ acre of saltmarsh here. This will be the largest installment of saltmarsh planted by SCDNR in a single location.

Aerial view of saltmarsh planting

Aerial view of saltmarsh plantingEstablishing green infrastructure, like this saltmarsh, as an initial line of defense against climate change is a necessity in vulnerable communities. But there’s no denying that a long-term plan is critical. With funding from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF), the Aquarium is working in partnership with other organizations to engineer a resilience plan to restore 293 acres of saltmarshes here and in surrounding flood-prone areas.

Preserving the landscape, history and culture of the historic Maryville township is not only an homage to Just, but a signal to future generations to dream big. For Al, Just opened his mind to the potentials of what can be. “E.E. Just represented the possibility that someone that looked like me, and also had the same family roots in the Lowcountry, could work toward the dream of becoming a marine biologist,” Al tells us. “So much of what young people limit themselves to is what they can envision and imagine from where they come from. Think about how many young people, BIPOC women and men, come from similar backgrounds as E.E. Just. Imagine how powerful it is to see what he was able to do.”

Al continues, “Unfortunately, the same cultural barriers that were present during E.E. Just’s life still exist in many ways. Given the prevalence of serious environmental issues, like global climate change, we need to be able to attract and retain the best minds in the world to help mitigate the greatest challenges facing humankind. In 2021, we should realize that talent and ability should never be defined by the color of one’s skin. E.E. Just is a great reminder of this truth, but despite all of this, there are still many lessons for us to learn from his life as we work to create a better future.”

Special thanks to Al George, Dr. Dionne Hoskins-Brown and Dr. Matt Gilligan and for their contributions to this story. To learn more about the life and legacy of E.E. Just, we recommend the book, “Black Apollo of Science: The Life of Ernest Everett Just” by Kenneth Manning.